Git Gud

Original author: Johnathan

Modified by Henry Loi (hchloi@connect.ust.hk)

Reference from HKUST-Robotics-Team-SW-Tutorial-2021

This document discusses more Git/Github features for you to git gud haha! at git. We recommend you to read through Git Basics before reading this.

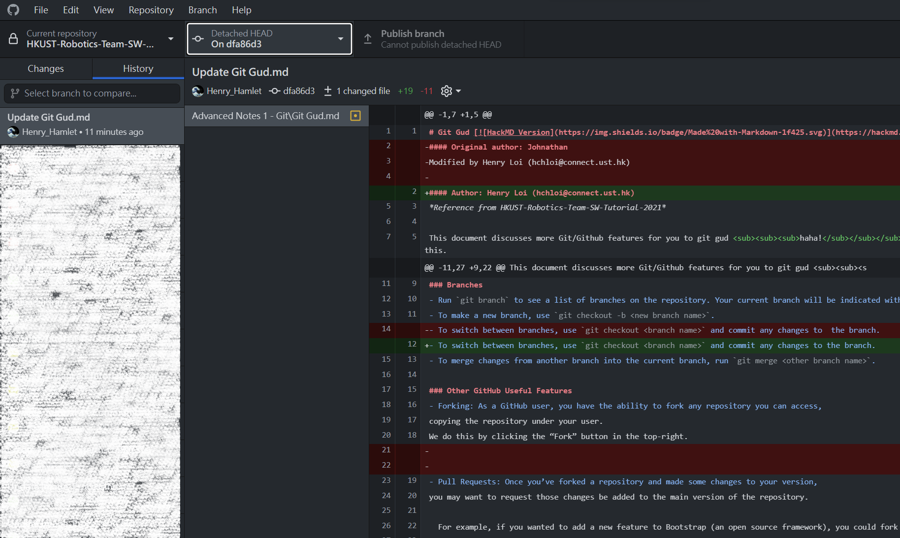

Branches

Run

git branchto see a list of branches on the repository. Your current branch will be indicated with an asterisk on the left.To make a new branch, use

git checkout -b <new branch name>.To switch between branches, use

git checkout <branch name>and commit any changes to the branch.To merge changes from another branch into the current branch, run

git merge <other branch name>.

Other GitHub Useful Features

Forking: As a GitHub user, you have the ability to fork any repository you can access, copying the repository under your user. We do this by clicking the “Fork” button in the top-right.

Pull Requests: Once you’ve forked a repository and made some changes to your version, you may want to request those changes be added to the main version of the repository.

For example, if you wanted to add a new feature to Bootstrap (an open source framework), you could fork the repository, make some changes, and then submit a pull request. This pull request could then be evaluated and possibly accepted by the people who run the Bootsrap repository. This process of people making a few edits and then requesting that they be merged into a main repository is vital for what is known as open source software, or software created by contributions from a number of developers.

Stash: By using stash, you can record the current state of the working directory and the index locally and go back to a clean working directory.

For example, when there are uncommitted changes in your current branch, you can't switch to other branches. Git stash temporarily shelves (or stashes) changes you've made to your working copy so you can work on something else, and then come back and re-apply them later on. Stashing is handy if you need to quickly switch context and work on something else, but you're mid-way through a code change and aren't quite ready to commit.

gitignore

When you make commits in a git repository, you choose which files to stage and commit by using git add FILENAME and then git commit. But what if there are some files that you never want to commit? It's too easy to accidentally commit them (especially if you use git add . to stage all files in the current directory). That's where a .gitignore file comes in handy. It lets Git know that it should ignore certain files and not track them.

A .gitignore file is a plain text file where each line contains a pattern for files/directories to ignore.

You can put it in any folder in the repository and you can also have multiple .gitignore files.

This will ignore any files named .DS_Store, which is a common, hidden file on macOS.

Directories

You can ignore entire directories, just by including their paths and putting a

/on the end

Wildcards

The * matches 0 or more characters (except /). So, for example, *.log matches any file ending with the .log extension. Another example is *~, which matches any file ending with ~, such as index.html~. You can also use ?, which matches any one character (except /).

Negation

You can use the ! prefix to negate a file that would be ignored.

In this example, example.log is not ignored, even though all other files ending with .log are ignored. But be aware, you can't negate a file inside an ignored directory:

Due to performance reasons, git will still ignore logs/example.log here because the entire logs/ directory is ignored.

Double Asterisk

** can be used to match any number of directories.

**/logsmatches all files or directories named logs (same as the patternlogs).**/logs/*.logmatches all files ending with .log in a logs directory.logs/**/*.logmatches all files ending with .log in the logs directory and any of its subdirectories.**can also be used to match all files inside a directory. For example,logs/**matches all files inside oflogs/.

Comments

Lines starting with # are comments:

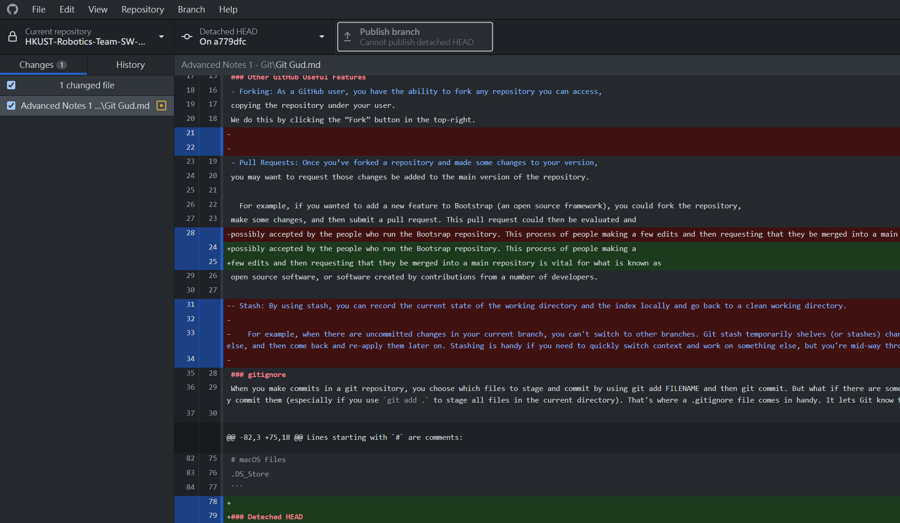

Detached HEAD

detached HEAD is a common situation when you use git. But if not handled properly it can result in your efforts going down the drain. Before you can understand what a detached head is, you must know what HEAD means.

About HEAD

HEAD is a pointer, and it points — directly or indirectly — to a particular commit:

Attached HEAD means that it is attached to some branch (i.e. it points to a branch). Detached HEAD means that it is not attached to any branch, i.e. it points directly to some commit.

Why I have to care about this?

Here is an example of detached HEAD.

You can see that in a deteached HEAD you can stil make changes and commit them.

However, when you change back to a branch, your commits will disappear.

What should I do?

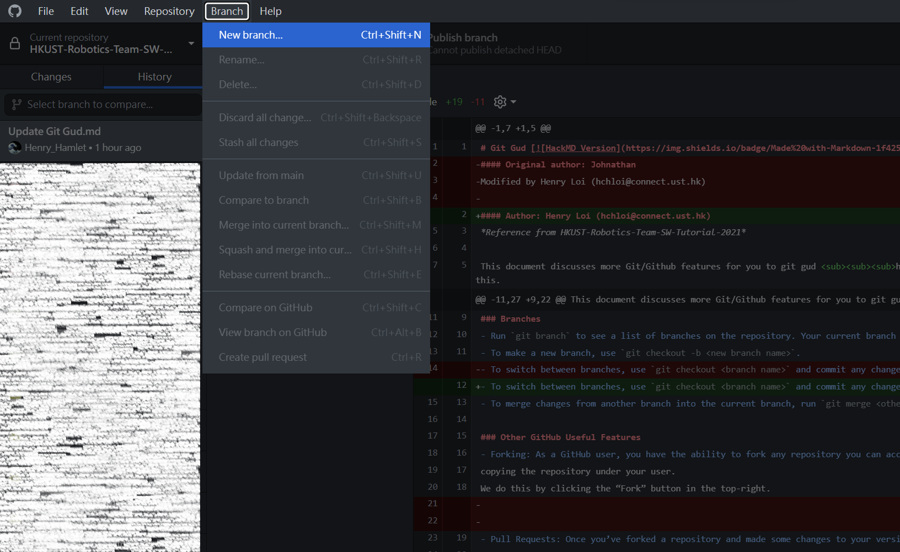

In order to prevent such tragedies from happening, please create a new branch when you want to make changes on a detached HEAD. Creating a new branch is the easiest way to solve this problem. You can even create a new branch after your commit is complete.

The worse case

The worse case is that you change to a branch from a detached HEAD with new commits. But don't worry, you can still find it by commands.

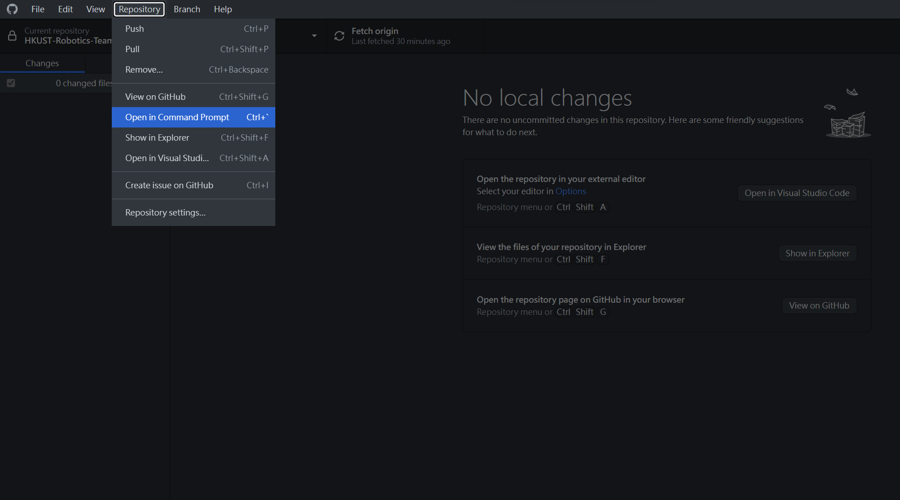

Step 1: Click Repository and press Open in Command Prompt

Step 2: Type commands

It will show the commit you made recently, include the one you made on a detached HEAD. Then you can get the ID of the commit you want to recover. For example:

After that, type

For Example:

Step 3: Create a new branch

Congratulations! You have kept the fruits of your efforts!

Last updated